A native Kansan returns home to find that the broken promises of commodity agriculture have destroyed a way of life.

Most Americans experience Kansas from inside their cars, eight hours of cruise-controlled tedium on their way to someplace else. Even residents of the state’s eastern power centers glimpse its vast rural spaces at 85 mph, if at all.

But on recent trips back, I wanted to really see my home state—so I avoided I-70, the zippy east/west thoroughfare. The slower pace paid off in moments of heart-stopping beauty. At dawn, outside Courtland, wisps of morning mist floated above the patchwork of farms that gently rolled out all around me. Driving up a slight incline, I had a 360-degree panorama to a distant horizon. And that is when I realized what was missing. As far as I could see, there was an utter lack of people. The only other sign of human life was a farm truck roaring down a string-straight road toward the edge of the earth.

Pictured above is a small section of Main Street in Wheaton, Kansas. The building of Kufahl Hardwarde, formerly Wilson and Kufahl, was founded in 1896. The upper level was a funeral home. There’s a giant wooden freight elevator, still in working order, that was used to lift and lower caskets. To the right of the sign on the corner is a red gas pump.

That’s the thing about rural Kansas: No one lives there, not anymore. The small towns that epitomize America’s heartland are cut off from the rest of the world by miles and miles of grain, casualties of a vast commodity agriculture system that has less and less use for living, breathing farmers.

U.S. census data tells the story. The population in most of Kansas’s rural counties peaked 50 years ago or earlier. The state’s annual population growth rate is among the slowest in the country, steadily falling from 1.2 percent in 1960 to 0.9 percent in 2016, with nearly all of that meager growth concentrated in a handful of eastern urban areas—Wichita, Kansas City, Topeka, and Lawrence.

Population is also growing in the areas around the state’s massive slaughterhouses and feedlots, which have built communities largely around immigrant labor. But that’s nowhere near enough to stave off the decline, which is only expected to increase more rapidly. Wichita State University forecasts Kansas’s annual population growth next year will fall by half again, holding steady at a paltry 0.4 percent for the next 40 years. Dozens of Kansas’s rural counties now average less than 10 people per square mile, while towns I remember from my childhood have almost completely collapsed. According to U.S. News and World Report, Kansas ranks 46th in net migration, and is losing 25- to 29-year-olds faster than any other state.

I wanted to know more. So I spent weeks visiting farms and main streets, and driving around the state’s back roads—more than 1,800 miles in total—to find out where everyone went, and why the last, remaining holdouts decide to stay.

Just south of Manhattan, Kansas at sunrise. Early morning fog from the Kansas River covers soybean and corn, dry crop fields farmed by small, local, independent farmers. This area is in a flood zone, with sandy soil in the valley of the Flint Hills, and scattered with trees

My journey began last December, with a journalistic lead—a story I felt sure would confirm my belief in the power of good food.

I’d learned that a group of nonprofits led by the Kansas Health Foundation had spent years studying the depopulation of rural Kansas. Their research had yielded one central finding: local food stores selling fresh produce help to stabilize struggling communities. Last November, the consortium unveiled an initiative implemented by Kansas State University that could deliver up to $10 million in grants to support such stores.

The spark for this initiative came from Marci Penner, a self-starter in Inman, Kansas (population 1,353) who publishes state guidebooks through her Kansas Sampler Foundation. After twice visiting each of the state’s 626 incorporated towns—half of which have fewer than 400 people—she has doggedly tracked the success of their food stores. In her view, a town’s ability to survive hinges on whether residents can buy healthy food there.

Penner’s goal is to get urban Kansans out to rural areas to support these struggling communities. “No one knows how to wrap their heads around these little towns. We are invisible,” she told me. “It’s time someone said, ‘I’m from Kansas. I’m sticking up for this state.’”

My bags were packed the minute I got off the phone. A story about Kansans determined to keep America’s breadbasket from becoming a food desert would write itself, I thought. But it was also an excuse to go back home. A fourth-generation Kansan on both sides, I found myself looking for a reason to return, and longing to drive through parts of the state I haven’t visited in decades. I could almost smell the Flint Hills wildflowers and see the wind’s invisible fingers moving through that ocean of bluestem grasses.

With a list of Penner’s favorite stores in hand and my daughter along to share the journey, I flew home.

We sensed the missing plot points in Penner’s folktale early on. Too many storeowners knew nothing about the grants. When we asked rural officials about the importance of grocery stores, they shrugged. Affordable housing, jobs, schools and hospitals topped their lists. Everyone wanted to talk about Kansas’s depopulation crisis, but a lack of healthy food, they all agreed, was not why people left.

Reality snapped into focus the morning we drove into Downs (population 844). I’d been in a close friend’s wedding there in the 1980s, and the tiny, one-street downtown had teemed with life back then. My friend’s father owned, edited, and published the local newspaper. Another friend’s dad ran a successful real estate company. It took those girls forever to walk anywhere; everyone wanted to stop and chat. Downs had 1,324 residents in 1980—36 percent more than it has today.

Kansas’s plentiful grain crop has come at the expense of nearly everything else.

Thirty years later, the blank faces of empty storefronts line the main drag. Oddly, one of the last remaining businesses we found was a well-stocked grocery store, though no one was shopping inside the brightly lit aisles. When we asked where we could get a cup of coffee, the cashier directed us to the gas station outside of town on the two-lane state road. A pot of brown water on a quick mart hot plate was the best the town had to offer.

Everywhere, I felt the absence—of people, of commerce, even of sound. The silence was broken only by a vintage pickup truck pulling up to the Downs grain elevator, huge mounds of excess grain piled high on the ground all around it.

That image—abundance at the center of a depopulated landscape—sums up the reality of rural Kansas. Yes, the harvest continues to be bounteous. But it masks a harder truth: Kansas’s plentiful grain crop has come at the expense of nearly everything else.

Donn Teske, president of the Kansas Famers Union

Feeding the world, at any cost

It’s hard to talk about Kansas without talking about wheat. In 2016, the state grew 467 million bushels across 8.2 million acres, an area almost twice the size of New Jersey. Hard Red Winter wheat, a hearty, versatile variety that dominates the landscape with its firm, tannish tassels, accounts for 95 percent of Kansas’s wheat acreage, which in turn represents 40 percent of America’s total Hard Red Winter crop. Most years, Kansas is the top U.S. wheat producer as well as exporter, contributing as much as 20 percent of the country’s overall crop—enough to pack a freight train stretching from the state’s western border all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. But Kansas is a major grower of other commodity crops as well. Between 2015 and 2017, only two states—Iowa and North Dakota—had more planted acreage. Almost 90 percent of Kansas’s total land area is devoted to agriculture.

Kansans worked for generations to transform the prairie grasslands into this solidly planted landscape. Farmers accepted that heritage until their communities began to shrivel and die.

“It’s getting lonely,” said Donn Teske, who farms near Wheaton (population 103). “It doesn’t make much sense to keep going, does it?”

Teske is president of the Kansas Farmers Union, and carries the weight of experience in his sigh—the same world-weariness I heard in other farmers’ voices as I traveled the state. For years, he’s watched friends and neighbors urge their children to go work in the city because the land doesn’t offer enough of a future. Now it appears they were right.

“I’ve been fighting this fight my whole life,” he told me. “Everything always works to help the big get bigger. I farm 1,000 acres,” he said, and that’s not big enough any more. Kansas farmers “are really good people and they’ve been fed a line.”

Commodity crop prices have fallen off a cliff.

The line I heard again and again on this trip, and throughout my childhood, is “Kansas farmers feed the world.” Both today and in years past, I heard this truism spoken with deep pride, a rationalization for all the hard work and money spent to keep improving yields. For some, though, this rural mantra has started to smack of a con. While farmers have toiled to increase output at every opportunity, they now are seeing their incomes fall in return.

Since 1980, the average Kansas farm has expanded in size from 640 to 770 acres—and yield increased, too, thanks to investments in machinery and chemicals. Between 2003 and 2016, Kansas’s farmers improved their wheat yields from 48 bushels/acre to 57 bushels/acre and enjoyed some record harvests, according to Mykel Taylor, a K-State agricultural economist.

But those extra bushels per acre likely required exorbitant financial investment. During those same years, Kansas’s average annual expenses per farm more than doubled, rising from $130,000 in 2003 to a whopping $300,000 in 2016, according to Taylor. And now, commodity crop prices have fallen off a cliff. Commodity wheat, for instance, fell to $3.37 per bushel in 2016 after averaging $6.50 per bushel across the previous eight years.

A large surplus grain storage facility just on the edge of Courtland, Kansas. This is surplus that hasn’t been, and/or can’t be sold yet. Across the street is an area the same in size filled completely with sorghum

The combination of soaring costs and plummeting prices has created an emergency in the nation’s breadbasket. “We are in our third year of very low farm income levels across the state,” said Taylor. Net income per operator fell to $8,451 in 2015. While it rebounded to $55,790 in 2016, it remains well below the $150,000 average of the previous seven years.

It is dark irony that, by focusing on production, Kansas farmers have devalued their own goods. Ever more sophisticated technology has led to a commodity grains glut that—thanks to the simple law of supply and demand—has crashed prices. In towns across Kansas, two- and three-year-old wheat sits under tarps beside full-to-the-brim grain elevators. Farmers wait in the hope that prices will rise—even just a little bit—before they sell.

“We’ve grown so much wheat we’ve dug ourselves into a hole after a run of good years,” said Taylor. The state is a victim of its own agricultural success.

When debt-saddled farmers can’t recoup their expenses, they can quickly have no choice but to sell their land—a painful decision that sometimes means leaving rural Kansas entirely. There were 75,000 farms in Kansas in 1980. Today, there are only 59,600, according to Xan Wedel, a researcher at the University of Kansas Institute for Policy & Social Research.

“Kansans are complacent. They accept the depopulation.”

But consolidation is not the only way commoditized farming exacts a human cost. The very purpose of today’s highly mechanized agriculture is to eliminate people from the farm system. After all, modern technology—from machinery to chemical herbicides to proprietary high-yield seed—allows one farmer to accomplish a task that would have taken three a generation ago. Today, operators sitting at computers hundreds of miles from the farm can easily steer gigantic harvesters via satellite. Kansas’s agricultural landscape needs fewer and fewer human caretakers.

Rural areas across the Great Plains “uniformly are experiencing decline,” said John Leatherman, an agricultural economist at K-State, the land grant university responsible for supporting Kansas’s agricultural sector. And, in his view, that’s not such a terrible thing. “Under-utilized human infrastructure”— schools and hospitals serving depopulated areas—is a burden on urban taxpayers, he said. “It is good for society and the world as a whole,” to move to a more robotic “factory floor” model of agriculture.

Not long from now, “the region will only need people to run the grain silos and the gas stations,” said Laszlo Kulcsar, head of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education at Pennsylvania State University. “Such people will not care about the place or the land. They will be people with no other options.”

For years, Kulcsar studied the depopulation of rural Kansas as director of K-State’s Kansas Population Center. In his view, commodity agriculture has squeezed all other economic life out of rural Kansas. But when he visited all of Kansas’s 105 counties on more than one occasion to speak with farmers and other residents about their lives, he found only resignation.

“Kansans are complacent,” he said. “They accept the depopulation. They think they are winning if they just slow it down. That’s not winning.”

Luke Mahin standing in the door frame of a hoop farm where tomatoes are being grown. As economic development director for Courtland, Kansas, Mahin has helped provide resources to farmers to produce these projects

A failure of policy

Luke Mahin grew up in Courtland (population 270), the geographic center of the lower 48 states. As Republic County economic development director, he is responsible for keeping his spot of north-central Kansas from going silent. This shouldn’t be a tough job, he told me: His internet-connected, foodie generation is full of farm kids eager to come home. Courtland has a local, organic farmer who uses hoop houses to keep the town supplied with fresh produce much of the year. Pinky’s is a local spot to gather at for coffee in the morning and beers in the evening—rare amenities for a town as small as Courtland. In theory, amenities like these could combine the best of the city with the perks of country living.

The problem is there are no jobs; everyone who wants to stay has to bring one with them. And, when people are in short supply, so is affordable housing. The cost of building or rehabbing a house cannot be recouped in a rural housing market stuck in free fall. I asked Mahin who he turns to for support. Who has his back? He paused a moment before answering that he often turns to small-town advocate Marci Penner. She tries to help, he said.

The state government? Not so much. Depopulation has lessened rural Kansas’s political clout, said Mike Matson, director of industry affairs and development with the Kansas Farm Bureau. Today, he said, the number of residents living in a few blocks of the Kansas City suburbs outweighs the population spread across 14 rural counties.

“We feel the prejudice in the cities against supporting small towns,” Mahin said. “Legislators hear people say ‘there’s no one out there,’ and they use that to cut support.” Despsite the fact that he’s a Republican, Mahin said he’s struggled to get the attention of the state’s Republican governor, Jeff Colyer, or anyone in the Republican-controlled Legislature.

The stakes are high. In 2012, former Kansas Governor Sam Brownback instigated a budget crisis by instating massive business tax cuts—state revenues plunged by $700 million, and education and infrastructure were slashed in response. These cuts were particularly hard on rural Kansas. While the State Legislature kept the state solvent by restoring two-thirds of those taxes last year, and will likely increase taxes again, programs targeting rural Kansas no longer exist, according to Duane Goossen, a senior fellow with Kansas Center for Economic Growth.

“Kansas is not in a position to mitigate the effects of rural depopulation. The state can’t invest in any of the programs that would help keep those communities healthy,” said Goossen. “All of the state’s political energy is going into making ends meet.” It will be a generation before the state returns to pre-2012 functionality, he said.

Main Street in Frankfort, Kansas, an old railroad town founded in 1867. Population: 726. Ninety-eight percent of the town is populated by white residents

Over chili at Hays House in Council Grove, (population 2,060), I spoke with former Kansas U.S. Senator Nancy Landon Kassebaum, age 85, who has retired to her Flint Hills ranch. She remains the gracious stateswoman I knew as an intern in her Washington office and was direct and matter-of-fact about the continuing depopulation of rural Kansas. “This has been going on a long time,” she said.

In Kassebaum’s view, more could be done to support small communities, but a lack of leadership in rural Kansas has stymied potential efforts. Besides, minds are not easily changed. “Kansas farmers are very good, very efficient,” she said. You could phrase her compliment another way: Kansans will cling proudly to commodity agriculture even as it destroys them.

Some of the people I spoke to—like Tom Giessel, a historian for the National Farmers Union—long for the days when the state had strong leadership in Washington. Between Kassebaum and former Kansas U.S. Senator Bob Dole, the state was a political powerhouse in the 1980s and 1990s, but those days have long since passed. “I just want to go back and hug them both,” said Giessel, who farms in south-central Kansas near Larned (population 3,900). He’s sure neither would be sitting on the sidelines. Today, he said, it’s a different story. “Kansas has no power in Washington anymore.”

That’s not going to change any time soon. Depopulation will likely continue to hurt Kansas’s stature on the national stage: The state is expected to lose a U.S. Representative seat—going from four to three districts—after the next census, or the following one.

With policy solutions in short supply, the future of rural Kansas increasingly depends on international trade deals. While the future is “bigger farms and fewer farmers,” said the Farm Bureau’s Matson, keeping international markets open to Kansas’s grain is critical to sustaining what’s left of the state’s farm communities. When I spoke with him back in January, the Bureau was pressing President Trump to break his campaign promise and keep the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) intact while pushing him to replace the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with new Asia deals.

This month, Trump further destabilized America’s farm communities by advancing a trade war with China. To make it up to farmers, among Trump’s most ardent supporters, the administration said it would consider rejoining the TPP. But that distant hope was dashed last week when Trump announced he would only consider bilateral trade deals with individual nations.

Cattle farm off of highway 99, between Frankfort and Wheaton, Kansas at sunset. It’s calfing season on the cattle farms and you can see two new baby cows here grazing alongside the senior cattle

The slaughterhouse as silver bullet

“It would appear we are headed toward zero,” conceded Don Hineman, majority leader of the Kansas House of Representatives and western Kansas farmer from Dighton (population 970). While he said he’s optimistic farmers will be part of the landscape of Kansas for another 100 years, Hineman did not deny the endgame. The state’s current economy has been particularly hard on his district. “We feel the pain more than the cities. With cuts in healthcare, schools, and highways, there is no work for our rural folks.”

And yet Hineman is one of many Kansans who believes there is a silver bullet: food-processing operations, mostly feedlots and slaughterhouses. Republican Congressman Roger Marshall agrees. His vast district, one of the geographically largest in the country, includes the western two-thirds of the state. Feedlots and meatpacking plants have made southwest Kansas an economic hot spot, he said. “We are growing so fast we can’t get enough people out there.”

Southwest Kansas is winning, according to Kulcsar, by accepting immigrants to work in local meat processing plants. Inside the beautiful new high school in Garden City, 31 different flags hang, each representing a country of origin for their students. “Economic infusion will come from people who are different culturally from the people who live in Kansas now,” said Kulcsar.

At times, the sources of this growth have laid bare another of Kansas’s cultural obstacles: xenophobia. “There is a vocal anti-immigrant minority in the state,” Hineman said, recognizing that Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach was the Trump administration appointee who promised—and failed—to prove that millions of illegal immigrants voted for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. Race is an increasingly fraught cultural rift. Eighty-five percent of Kansans describe themselves as “white alone,” according to KU’s Institute for Policy & Social Research—11.5 percent whiter than the country as a whole. Wichita, the state’s largest city and home to Koch Industries, is a rare American city that is growing whiter—up three percent in the last five years with 76.2 percent self-defining as “white alone.”

Regardless, said Hineman, “most Kansans understand this is the workforce we need most” if the state is going to expand its population.

Which is one reason Congressman Marshall bristled at any mention of rural depopulation or a depressed farm economy. The Kansas economy is booming, he insisted, carefully sidestepping any mention of the state’s rural/urban divide. His chosen indicator of its vibrancy is the state’s 50,000 unfilled jobs. But when I asked for a copy of that jobs report, I received a spreadsheet showing 27,716 open jobs in Kansas—the vast majority in the state’s few urban areas. In the western two-thirds of the state, which includes the thriving meatpacking zone, the KansasWorks.com report lists 3,685 unfilled jobs.

Marshall is emphatic, however, that his district needs no additional state or federal help. “I think communities can solve their problems better for themselves,” he said, voicing a common Kansas sentiment. “I believe in American ingenuity and the American spirit.”

But even that optimism may contain a form of denial: Critics allege commodity food processing, such as meatpacking, suffers the same shortfalls that make commodity crop farming unsustainable.

Industrial meat processing offers no more secure future than industrial agriculture, said Don Stull, KU professor emeritus of sociocultural anthropology, who has studied the meatpacking industry for 30 years. In his view, both systems tend to grind communities up in their ceaseless push for lower costs and fewer workers.

Dozens of Kansas’s rural counties now average less than 10 people per square mile.

The state’s farmers accept a system that forces them to pay ever higher prices for farm inputs and offers them no options for selling their grain except commodity markets where they have no control over price, Stull said. Industrial food processing is the same no-win game—and not just because feedlots and meatpacking plants pollute surrounding land. They, too, are subject to the precarious rise and fall of global commodity trading. They, too, tend to treat human workers like cogs, in a push for ever-greater efficiency that’s likely to lead to increased automation.

“We understand what these plants do to the environment, to the quality of rural life,” said Stull. Yes, individual counties and the state could demand higher environmental standards, demand these companies treat workers and animals better. But, in Kansas, it may not be feasible to impose more regulation on farms and processors. Stull said it would mean “falling on your sword”—political suicide.

“I’m not optimistic,” he said.

In other words, business as usual.

Frankfort, Kansas, looking straight down Main Street. Pictured are the main rail lines, grain elevators, old water tower, and church steeple popping up from the trees

Help wanted

Across Kansas, a lonely few are trying to pivot away from the system of industrial agriculture that has defined, and drained, the state.

I met Tim Raile at Fresh Seven Coffee in Saint Francis (population 1,300), at the suggestion of owners Kale Dankenbring and his wife, Heidi Plumb. After a cup of their coffee, our first cup of the trip that didn’t come from a gas station, I trusted their taste.

In the most remote northwest corner of the state, Dankenbring’s hometown, the couple built a motorcycle repair shop and coffee house with graffiti art and used furnishings suitable for any hangout in Los Angeles or Brooklyn. In five short years, they became the glue holding this struggling farm community together. Raile is a regular, as are most of the farmers, their wives, and the town’s two cops. “People who have never left rural Kansas just see the limitations,” said Dankenbring, who brought Plumb, with her coffee roaster, home with him after they traveled the world together.

Like most of the farmers in Cheyenne County, Raile has been a conventional commodity grain farmer his whole life, as were his father and grandfather, one of the original group of German farmers immigrating to America from Russia who built the town at the turn of the century.

Going organic is the ultimate contrarian move for a Kansas farmer.

But as Raile said: “When everyone zigs, I zag.” He has always been quick to try new seeds, new herbicides, and new machines, and was an early adopter of no-till farming. While other northwest Kansas farmers were draining the Ogallala Aquifer to irrigate thirsty cornfields, Raile dry farmed. He likes to bet against the crowd.

Easy-to-spray herbicides and pesticides made it possible for Raile to handle his 8,500-acre farm by himself, only recently bringing his son on to help. But one year, his cocktail of herbicides left a few weeds. The next year, and each year thereafter, more weeds survived. In a few years, weeds were overwhelming his wheat fields. “It didn’t matter what chemicals we used or how much,” he said.

When his annual herbicide bill hit $250,000, Raile feared he was killing his farm in an effort to protect his income. “I quit arguing with reality,” he said. “This wasn’t sustainable.” He switched to certified organic agriculture.

Going organic is the ultimate contrarian move for a Kansas farmer. Raile kept his decision a secret from even his closest friends that first year. Less than one percent of Kansas’s agricultural production is certified organic—that’s a mere 86 farms with a total of 54,208 certified organic acres, as of 2016, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). In a state with $18 billion in annual agricultural product sales, the 60 members of the Kansas Organic Producers Association have recorded a mere $8 million in annual sales for the last several years.

Disdain for organics runs deep among Kansas farmers, said Raile. Two and a half years into his transition to organic, just one friend has stopped by to ask him about switching.

“There are plenty of good reasons to not go into organics,” he said. It’s labor intensive, which means hiring farmhands. He had to buy new equipment and learn new farming methods. Still, he thinks the math is in his favor with the money he’ll save on chemicals.

“I’ve always believed the big ag companies when they said their chemicals are safe,” he told me. And he chooses to continue to not question that trust. But if consumers are paying a premium for organics—two to four times the price of commodity wheat, depending on the grain —he thinks it’s crazy not to grow it for them. He plans to sell directly to customers along the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, a three-hour drive from Saint Francis, where demand is high for organic heritage grains.

Raile isn’t alone, said Catherine Greene, USDA senior agricultural economist. With commodity grain prices falling, there has been a spike in conventional grain farmers switching to organics. “It’s a higher value crop, which is why organic acreage is increasing around the world,” she said.

Raile is not the first St. Francis farmer to go organic. Robert Klie flipped his 2,100 acres to organics 13 years ago and said he earns $22/bushel for heirloom Turkey Red wheat and $10/bushel for his standard organic wheat. “When the chemicals don’t work, the company always has an excuse,” said Klie. That ticked him off. One day he stopped using chemicals cold turkey. “Chemical companies have brainwashed farmers, telling them they are feeding the world and they can’t do it without all of these chemicals. Well, you can do it without chemicals. We are,” he said.

“We have got to develop more specialty agriculture in this region. Our traditional life is ending as the price of grain goes down.”

Back at Fresh Seven, Plumb told me about Nina and Jeter Isley, whose Y Knot Farm & Ranch uses hoop houses to grow fresh organic produce seven months of the year. She serves their vegetables in her salads and sandwiches. She also made friends with Mike Callicrate, an outspoken local regenerative rancher with progressive ideas about overhauling America’s food system, and started serving burgers made with his ground beef.

Bob Klie and the Isleys are members of The High Plains Food Cooperative, 20 or so local food producers who have developed a market for their products in the Denver, Colorado area where Raile hopes to sell his organic grain. The co-op’s annual sales are close to $400,000, showing enough success that the non-profit city foundation in neighboring Bird City, Kansas plans to build them a food processing facility.

“We have got to develop more specialty agriculture in this region,” said Rod Klepper, a retired businessman who has made revitalizing northwest Kansas a personal mission. “The window of opportunity is closing fast out here. Our traditional life is ending as the price of grain goes down. We spend more pumping up the fertilizer and herbicide to increase yields and the price falls further. That’s the spiral we’re in.”

What began as a market-driven decision, Raile said, has changed his philosophy about farming and caring for his soils and the environment. He joined the Organic Trade Association (OTA) and went to Washington, D.C. to lobby Republican Senator Pat Roberts for changes in the 2018 farm bill that would put new organic growers on par with conventional farmers when it comes to federal farm insurance, hoping to encourage more conventional farmers to switch.

Raile hopes to push K-State to teach organic agriculture. Currently, the university offers no—as in zero—organic agriculture classes, a common situation with land grant schools dependent on corporate underwriting.

“Tim is pushing the envelope,” said Laura Batcha, OTA’s executive director. “The central part of the country is one of the least developed areas for organics,” a fact she believes could change with Raile’s leadership. Organic agriculture creates “hot spots” of economic activity, she said, increasing the number of jobs, raising wages, and reducing poverty across a region.

Luke Mahin, Republic County’s economic development director, agreed. He told me he wishes he could convince Courtland’s commodity farmers to start growing specialty crops such as produce, organics, and heirloom grains. “Commodity crops are a race to the bottom,” he said. It’s an agricultural system that kills jobs instead of creating them.”

Raile expects to hire two additional farmhands, both of whom will need advanced educations to handle the technology he plans to use. That’s not enough to turn around the local economy, but it does make Raile a rare Kansas farmer who hangs a “help wanted” sign on his door.

Kansas’s predominately German heritage settlers survived holy hell—disease, clouds of giant grasshoppers, epic thunderstorms and blizzards, years of drought, and then the Dust Bowl. Gold diggers and gamblers moved on. Sodbusters and schoolteachers stayed to hoe their rows.

Many of today’s farmers are direct descendants of those original pioneers. Alone and in silence, they are bearing witness to the emptying out of their communities and the disappearance of their ancestors’ legacy. But, like so much about Kansas, it doesn’t have to be that way.

Across Kansas, small towns have established food policy councils working to build resilient food and agriculture economies in the absence of coherent federal and state-level leadership. And the fact that Kansans have partially restored their state business taxes and are moving, fitfully, toward insuring the future of their public schools gives me hope for their future. Focusing on the next generation is always a good place to start. But blind faith in outdated agricultural orthodoxy and a failure to imagine a new way forward for farmers still dominates rural policy.

If only Kansans were as fiercely independent and self-reliant as they claim to be. They might take a stand to preserve their own future. They might step away from the herd to consider new ideas. With more self-confidence, they might believe the approach to agriculture that’s disserved them can be changed for the better.

They might even show the world outside Kansas why this singular place, with its particular culture, is worth cherishing—giving passers-through a new reason to slow, roll down their windows, and decide to stay a while.

Original photography for this piece was shot by Luke Townsend, a street and cultural photographer based in Manhattan, Kansas. See more of his work here.

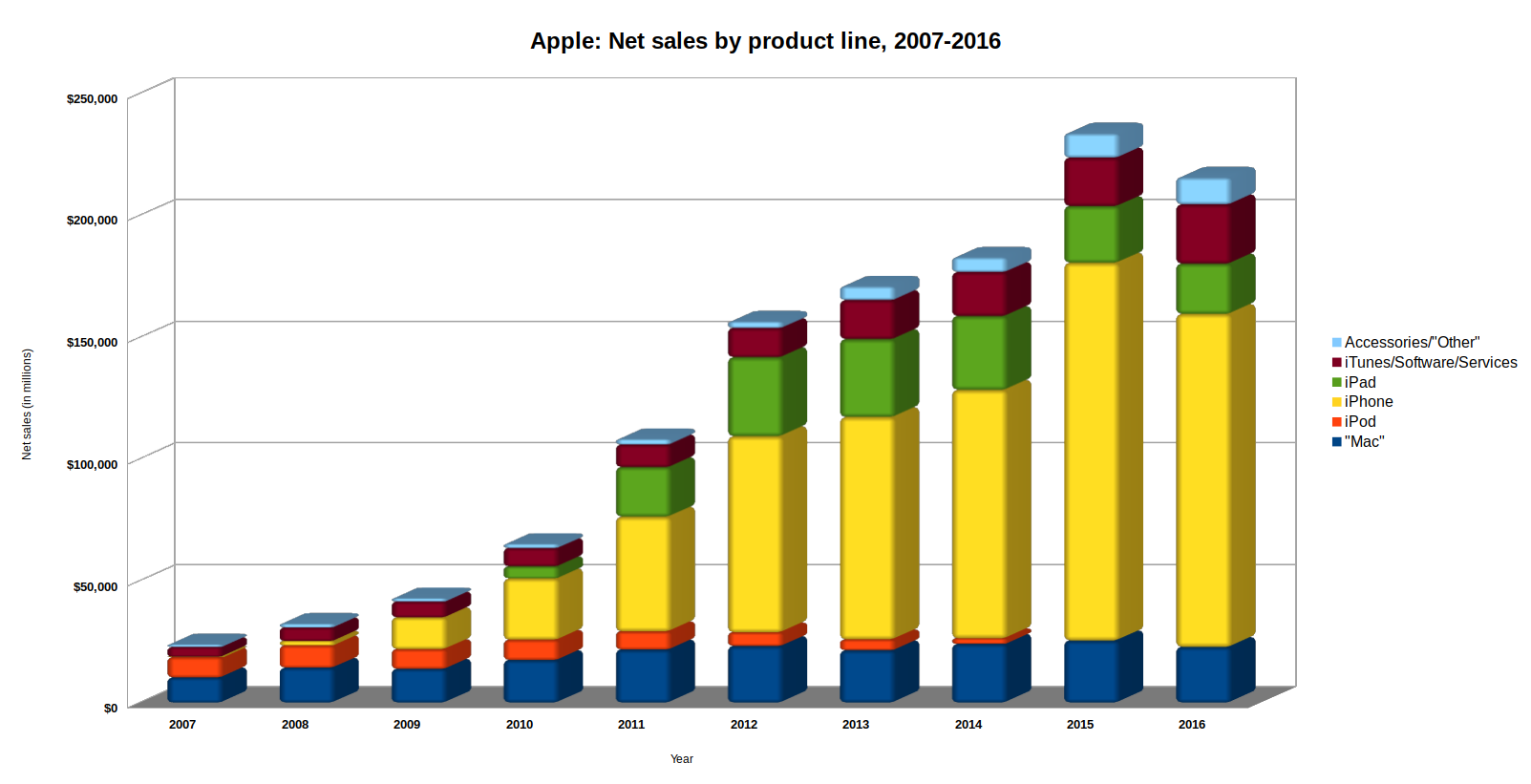

So last week Apple rolled out its newest version of the venerable MacBook Pro, and the world of creative professionals who use Macs promptly freaked out as it became clear that the revision wasn’t going to address any of the concerns over Apple’s product direction that have been simmering in that world for a few years now.

So last week Apple rolled out its newest version of the venerable MacBook Pro, and the world of creative professionals who use Macs promptly freaked out as it became clear that the revision wasn’t going to address any of the concerns over Apple’s product direction that have been simmering in that world for a few years now.

Humans Evolved But Are Still Special

Humans Evolved But Are Still Special