The older I get, the more I’m convinced that time is money (and money is time). We’re commonly taught that money is a “store of value”. But what does “store of value” actually mean? It’s a repository of past effort that can be applied to future purchases. Really, money is a store of time. (Well, a store of productive time, anyhow.)

Now, having made this argument, I’ll admit that time and money aren’t exactly the same thing. Money is a store of time, sure, but the two concepts have some differences too.

For instance, time is linear. After one minute or one day has passed, it’s irretrievable. You cannot reclaim it. If you waste an hour, it’s gone forever. If you waste (or lose) a dollar, however, it’s always possible to earn another dollar. Time marches forward but money has no “direction”.

More importantly, time is finite. Money is not. Theoretically, your income and wealth have no upper bound. On the other hand, each of us has about seventy (maybe eighty) years on this earth. If you’re lucky, you’ll live for 1000 months. Only a very few of us will live 5000 weeks. Most of us will live between 25,000 and 30,000 days.

I’ve always loved this representation of a “life in weeks” of a typical American from the blog Wait But Why:

If you allow yourself to conduct a thought experiment in which time and money are interchangeable, you can reach some startling conclusions.

Wealth and Work

When I began to fully grasp the relationship between money and time, my first big insight was that wealth isn’t necessarily an abundance of money — it’s an abundance of time. Or potential time. When you accumulate a lot of money, you actually accumulate a large store of time to use however you please.

And, in fact, this seems to be one of the primary reasons the Financial Independence movement is gaining popularity. Financial Independence — having saved enough that you’re no longer required to work for money — provides the promise that you can use your time in whichever way you choose. When I attend FI gatherings, I ask folks what motivates them. Almost everyone offers some variation on the theme: “I want to be able to do what I want, when I want.”

To me, one of the huge ironies of modern society is that so many people spend so much time to accumulate so much Stuff — yet never manage to set aside anything for the future. Why is this?

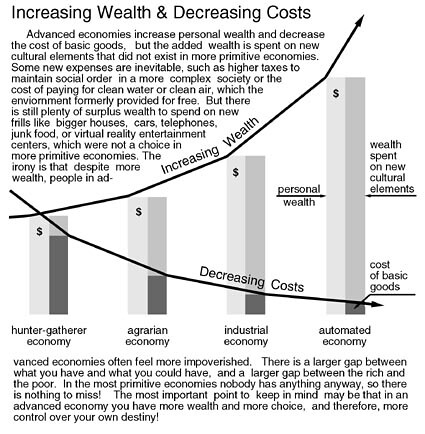

In an article on Wealth and Work, Thomas J. Elpel explores the complicated relationship between our ever-increasing standard of living and the effort required to achieve that level of comfort.

Ultimately you are significantly wealthier than before, but you are also working harder too. Nobody said you had to pay for oil lamps and oil or books and freshly laundered clothes, but you would feel deprived if you didn’t, so you work a little harder to give your family all the good things that life has to offer.

It’s a catch-22. You work more to have more money to buy more Stuff…but because you have so much Stuff, you need more money, which means you have to work more. It’s almost as if the more physical things you possess, the less time you have.

How do you escape this vicious cycle? There are two ways, actually.

Spend Less, Live More

The first (most obvious) way to remove yourself from this hedonic treadmill is to deliberately reduce your spending so that it’s below the level needed to maintain your lifestyle. As I’ve argued before at Get Rich Slowly, frugality buys freedom.

When you reduce your lifestyle, it takes less time to fund it. If you’re earning $50,000 per year take-home and spending all $50,000, you leave no margin for error. If something goes wrong — you lose your job, inflation skyrockets — you’re in a bind. Plus, you don’t give yourself a chance to seize unexpected opportunities!

But if you reduce your spending to $40,000 per year, you give yourself options. You can choose to continue earning $50,000 and bank the difference (building a store of time) or you can choose to work less today (taking the advantage of the time savings immediately).

Spending less also helps fund your future. Learning to live with a “lesser” lifestyle means you don’t need to save as much for retirement. If you spend $50,000 per year, for example, then you need roughly $1.25 million saved before you can retire. But if you decrease spending to $40,000 per year, your target drops to around $1 million.

It takes much less work to fund an ongoing lifestyle of $40,000 per year than it does to maintain a lifestyle that costs $50,000 per year. And if you’re in the fortunate position where you can slash your lifestyle from, say, $120,000 per year to $30,000 per year, you can really reduce the time you spend working.

Buying Time Promotes Happiness

But what if you like your lifestyle and don’t want to cut back? Or what if you’re not able to cut back? There’s still a way to use the relationship between time and money to increase your sense of well-being.

Last year, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal published an interesting article that declared buying time promotes happiness. The authors conducted a series of experimental studies to look at the link between time, money, and happiness. Their conclusion?

Around the world, increases in wealth have produced an unintended consequence: a rising sense of time scarcity. We provide evidence that using money to buy time can provide a buffer against this time famine, thereby promoting happiness.

Using large, diverse samples…we show that individuals who spend money on time-saving services report greater life satisfaction. A field experiment provides causal evidence that working adults report greater happiness after spending money on a timesaving purchase than on a material purchase.

Together, these results suggest that using money to buy time can protect people from the detrimental effects of time pressure on life satisfaction.

If you want to improve your quality of life, don’t use your money to buy Stuff, use it to relieve “time pressure”. Instead of buying a fancy car, purchase time-saving devices. Hire a housekeeper or a yard-maintenance company. Maybe consider a meal-delivery service.

Interestingly, the effects of “buying time” have the greatest impact on folks who have less money: “We observed a stronger relationship between buying time and life satisfaction among less-affluent individuals,” the authors write.

Finding Balance

My biggest takeaway from thinking about the relationship between time and money is this: When you spend less, you can work less. In a very real way, frugality buys time. But on a deeper level, frugality buys freedom — financial freedom, freedom from worry, freedom to spend your time however you choose.

When you treat time as money (and money as time), you can better evaluate how to allocate your dollars and your hours. When you know how much your time is worth, you can decide when it makes sense to “outsource” specific jobs.

Ultimately, there’s a balance to be had, and that balance is different for each of us. You have to decide how much time you’re willing to spend on present comfort and how much time you want to bank for the future. I believe there’s no single right answer to this dilemma.

What about you? How do you view the relationship between time, money, and happiness? Do you have some examples from your own life of buying time in order to improve your happiness? What balance have you arrived at — and how did you get there?

The post The relationship between time, money, and happiness appeared first on Get Rich Slowly.

from Get Rich Slowly https://ift.tt/2CLrqRA

via IFTTT