“SELL in May and go away,” say the denizens of Wall Street, and to the usual summer lethargy is added the excuse of a heatwave. But for those working in private equity, there is no let-up. The “shops”, as private-equity funds like to call themselves, are stuffed with money and raising more: $1.1trn in “dry powder” ready to spend around the world, according to Preqin, a consultancy, with another $950bn being raised by 3,050 firms.

So hot is the market that there are rumours of money being turned away. Even the firms themselves, which receive fees linked to assets under management, cannot fathom how to use all that may come their way. It is not for want of trying. The year to date has seen nearly 1,000 acquisitions (see chart 1). Health care has been particularly vibrant (see next article).

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Even more noteworthy than the volume of money pouring into private equity is the way the business is maturing. Banks are reconfiguring their operations to serve such a transaction-heavy clientele. Limited partners—the public-pension schemes, sovereign-wealth funds, endowments and family offices that provide the bulk of private-equity investment—are playing more active roles. It all adds up to a stealthy, but significant, reshaping of the financial ecosystem.

Data on returns are patchy. Odd measures are often used to gauge performance and disclosure is intermittent. But there is plenty of reason to believe that private-equity funds have done well in the past decade. Low interest rates have favoured their debt-heavy business model. Rising asset prices have made it easy to sell for large gains.

And some recent clouds on the horizon have dissipated. Mooted tax reforms would have stopped private-equity firms from deducting the interest they pay on debt from their taxable income and forced their managers to pay the personal-tax rate on their investment profits (or “carried interest”), rather than the lower capital-gains rate. In the event, however, the new rules brought in last year did not touch carried interest at all and only slightly reduced the benefits of debt.

Another fear had been that regulations would become less supportive. Jay Clayton, who took over at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) last year, made it clear that he wanted to see a shift towards public markets. He noted that the loss of companies to private equity had denied opportunities to small investors. A flurry of public offerings followed his appointment, including sales by private-equity firms. But the burdens of being listed remain heavy. These include onerous filing requirements and the knowledge that routine business decisions may become the subject of caustic public debate.

The result is that the value of public companies being taken private continues to rise (see chart 2). The figures understate the trend, since they omit the growing number of large companies selling off divisions to private-equity firms. These deals attract little attention—which is partly the point. Headquarters do not move; senior executives keep their jobs. Recent examples include the decision by J.M. Smucker, a food company, to sell its baking business to Brynwood Partners and GE’s move to sell its industrial-engines division to Advent International. Similarly unremarked is the rising number of transactions in which one private-equity firm sells to another, rather than listing an asset on the public markets.

Private equity’s growing heft has knock-on effects throughout the financial sector. Goldman Sachs has 25 merger bankers assigned to private-equity firms, working on deals alongside colleagues who focus on specific industries. Its analysts monitor 5,500 private-equity holdings—50% more than the number of listings on the American public markets. The other big institutional banks, such as Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase, are just as attentive to private equity.

The most significant change may be in private equity’s investor base. In the past two years the number of limited partners with more than $1bn invested has grown from 304 to 359. Together they account for $1.5trn—half of all private-equity money, according to Preqin. And this statistic does not fully capture their growing activism. As well as placing cash in private-equity funds, they increasingly “co-invest”—ie, take direct stakes in a buy-out.

The advantage for limited partners is that they avoid management fees—often 2% annually, plus 20% of profits. Private-equity funds gain from being less reliant on each other. Not long ago, large deals often required several funds to collaborate. The purchase of Nielsen Media in 2006, for example, involved seven. That alarmed antitrust regulators, complicated management and made it hard to exit from investments, since many potential buyers were already co-owners. The value of deals done by more than one private-equity firm has fallen by half since the Nielsen deal. Even when firms work together, the average number involved is smaller than it was.

For the biggest deals, private-equity firms are today making acquisitions solo and then syndicating large stakes through co-investments to limited partners. Notable among numerous recent examples are Blackstone’s purchase of Thomson Reuters’ finance and risk division in January for $20bn, and Carlyle’s of the specialty-chemicals division of Akzo Nobel, a Dutch multinational, in March for $12bn. The process often begins with a phone call by a private-equity firm to big, sophisticated investors such as GIC, Singapore’s sovereign-wealth fund, or CPP Investment Board, a giant Canadian pension fund. They can quickly put together teams to analyse transactions. Smaller limited partners are brought in later if needed, along with select outsiders, notably family offices.

This trend does not just reduce risk for private-equity managers. It also underlines a change in financial markets. Why should companies accept the costs and scrutiny that come with selling shares to the general public when there is a sophisticated, rich, private alternative? And when the time comes for one private-equity owner to sell, another private-equity fund can put together such a network to buy. Brokers and exchanges developed a century ago to help companies tap money where it lay—in individual pockets. Today that capital increasingly lies elsewhere.

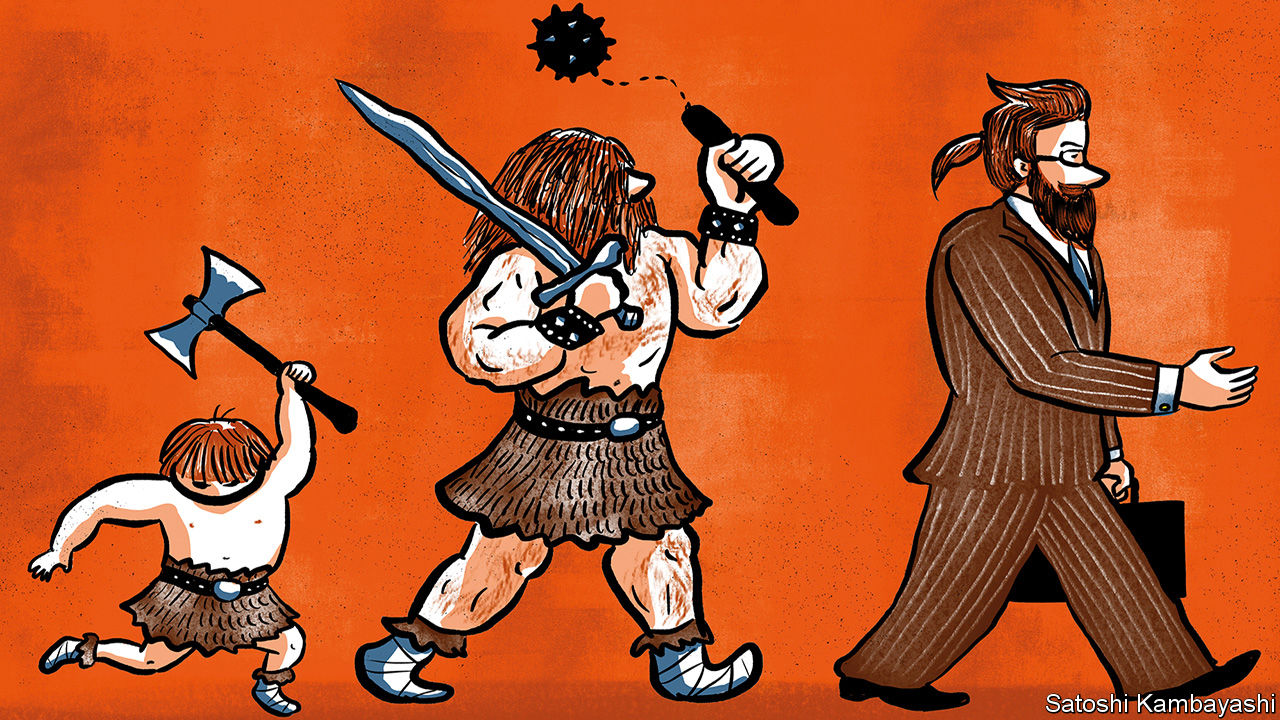

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline "Barbarians grow up"from Finance and economics https://ift.tt/2CXjJ08

via IFTTT